Disney+ recently released a series called, Suspect, which is a dramatisation of the events leading up to the tragic killing of Jean Charles de Menezes by the MET Police at Stockwell tube station.

I remembered that period in London when the whole capital was on high alert, the nervous glance and suspicious looks on public transport. I was working at University College London at the time and was close enough to hear the explosion at Tavistock Square on 7/7. I was attending a training course, the boom made everyone pause, it sounded like something really heavy hitting the floor a long way away, some remarks were made but we carried on. A short time later one of the other delegates shared that there had been an explosion, we stopped the session and were advised to return to our offices to stay in place until further instruction. Three tube bombings and one bus bombing happened that day. My Mum, Dad and brother all worked in London at that time and my immediate concerns were for their safety, I remember wanting to check they were OK, but you just couldn’t get through to anyone on your mobile phone (eventually I did get through and thankfully everyone I knew was OK).

Watching Suspect brought back those memories. The horror that some people went through, the heroic scenes of members of the public helping each other, and emergency workers running from the hospital with beds to do what they could to help.

Suspect brought into sharp focus what happened just weeks later when the MET Police killed an innocent man on the tube. He was not challenged; he was not wearing a big jacket and did not jump the barriers as earlier media reports had said. He was just a normal guy going to work quietly, quite unremarkable, unaware he was under surveillance and probably confused by the sudden rush of activity and why he was being singled out, by whom, until his tragic end.

In Human Factors education and training we often use real life case studies to highlight what went wrong and to explore lessons learnt. I wanted to use this case study as something different to the industrial accidents we look at like Piper Alpha and Texas City disasters. I also wanted to use it to explore aspects of the TABIE (Task Based Incident Evaluation) technique which we have been talking about more within HRA.

This blog is for educational and analytical purposes only. It is only based on publicly available information, particularly Suspect which itself is a Disney+ dramatisation. It is in no way intended as a comprehensive investigation and should not be considered a definitive account of events. The author acknowledges the profound tragedy of this event and its lasting impact on Mr. de Menezes’s family and all those affected. This analysis is conducted with respect for all involved and with the intent of contributing to better understanding of how systematic approaches to incident analysis might help prevent tragedies in the future.

TABIE’s Accident Sequence and Precursor (ASAP) Model: Beyond the Moment of Failure

Most incident investigations focus on the dramatic moment when things go wrong – the explosion, the collision, the fatal decision. But what if the real story begins months or even years earlier, in boardrooms, training centres, and policy meetings where the seeds of disaster are unknowingly planted?

As safety expert James Reason observed: “The role of the operator in an accident is to add the final garnish to a lethal stew whose ingredients have been long in the cooking.” This powerful metaphor captures a fundamental truth that traditional incident analysis often misses – the person who makes the final, tragic error is rarely the true cause of the disaster.

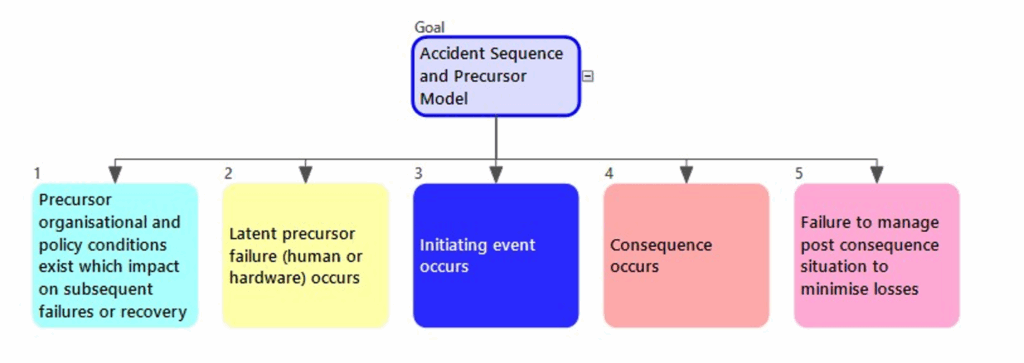

The Accident Sequence and Precursor (ASAP) Model, central to TABIE methodology, recognises a fundamental truth: major incidents are rarely caused by single failures in the moment. Instead, they result from the alignment of multiple weaknesses that have been lurking in the system – what safety experts call “latent conditions” – combined with active failures that trigger the final sequence.

ASAP maps incidents across five critical stages:

- Precursor Organisational Conditions – The deep-rooted policies, cultures, and resource decisions that create vulnerability.

- Latent Precursor Failures – Specific human or technical failures that create hidden weaknesses.

- Initiating Event – The trigger that activates the accident sequence

- Consequence – The immediate harmful outcome

- Post-Consequence Management – How the organisation responds, learns, and either prevents or enables future incidents

This model reveals why traditional “root cause” analysis often fails: it assumes there’s a single root to find, when in reality, major incidents grow from multiple roots that intertwine over time. By mapping the full timeline from organisational precursors to post-incident learning failures, ASAP helps investigators understand not just what happened, but why the system was vulnerable to this type of failure – and crucially, how to prevent it from happening again.

The power of ASAP lies in its recognition that today’s incident is often the result of yesterday’s policy decisions, last month’s training cuts, or last year’s technology choices. It transforms incident investigation from a reactive blame exercise into a proactive system improvement opportunity.

Redescribing the Stockwell Shooting using the ASAP Model

1) Precursor Conditions: The foundations of tragedy

After 9/11, Operation Kratos emerged when police realised they needed new tactics for suicide bombers. A Metropolitan Police team visited Israel, Sri Lanka and Russia, developing tactics including firing shots to the head without warning. The rationale was stark: suicide bombers would detonate upon realising they’d been identified, so police must ensure immediate incapacitation.

By July 22, 2005, this created a perfect storm. The failed 21/7 attacks meant suspects were still at large – CCTV images were released that very morning de Menezes was killed. Active terrorist cells remained in London, potentially planning further attacks, the threat felt imminent. After 7/7, specialised units had been reminded of Kratos tactics via internal email.

This transformed Kratos from theoretical policy into high-stakes reality. The pressure to prevent another mass casualty event, combined with an untested shoot-to-kill policy, created precursor conditions for tragedy. Organisational culture had shifted: preventing 7/7 attack with mass casualties appeared to take precedence over killing an innocent person through mistaken identification.

These precursor conditions – an untested lethal force policy, unprecedented threat levels, and enormous pressure to prevent further attacks – created a system primed for failure.

2) Latent Precursor Failures: Set up to fail

On July 22nd morning, a cascade of operational failures created the immediate conditions for tragedy. Surveillance began at the wrong address – targeting flat 17 when suspect Hussain Osman lived elsewhere, while de Menezes lived at flat 21. When de Menezes emerged, the primary surveillance officer was indisposed, leaving coverage compromised.

Identification became a game of percentages rather than certainty. Officers used language like “possible” match, there was disagreement with the likely match, perhaps one saying no, one saying yes, and another saying they couldn’t say it wasn’t him. Command asked for a percentage confidence but surveillance said that wasn’t possible. No clear threshold existed for authorising lethal force. Poor-quality photographs made positive identification even more challenging.

Critical miscommunications followed. There was confusion about whether to wait for armed CO19 officers before allowing the suspect to board public transport. No clear decision was made to stop de Menezes before he boarded the bus toward central London. Bus services weren’t suspended – as one officer requested – Command feared this would tip off genuine bombers that operations were underway.

Radio failures compounded the events, meaning coordination between surveillance, Gold Command, and firearms teams was more challenging. By the time de Menezes entered Stockwell station, the system had accumulated multiple failures: wrong intelligence, ambiguous surveillance reports, failures in identification, communication breakdowns, and missed interception opportunities.

Suspect shows that the armed officers were briefed twice about a potential Kratos operation that morning (part of the reason they were late) and they were given special ammo. The intention was to fully prepare them for these unusual circumstances, but in doing so it seems they were also primed for things to escalate. They were given discretion to use lethal force against an enemy that is willing to kill themselves, the officers and innocent by-standers. Just a small movement by the bombers could set something off and they were told the bombers did not need a backpack.

Each failure was individually manageable, but together they created the classic “Swiss cheese” alignment – multiple defensive layers failing simultaneously, creating a direct path to tragedy.

3) Initiating Event: The point of no return

The critical moment came when de Menezes approached Stockwell station. Despite uncertain identification, he wasn’t stopped – unclear whether CO19 officers had arrived and a decision was made to wait rather than have surveillance officers approach him directly.

Armed officers were running late, rushing to catch up while poor radio communications fragmented coordination. All precursor conditions and latent failures had now aligned: untested Kratos policy, post-7/7 pressure, wrong intelligence, compromised surveillance, and percentage-based identification.

Watching Suspect it is remarkable how sometimes subtle communication failures in the heat of the moment contribute to events. For example, they depicted someone saying that Nettle Tip (the callsign for the actual suspected bomber) was on the tube. Also, when Command was asked whether they wanted to stop the suspect they in turn asked where CO19 were and were told they had just got to the station. So the order was given for CO19 to stop the suspect, but the reality was ‘the station’ suggested they were collocated but they weren’t, only surveillance were in a position to act in that moment. Terms like ‘the suspect’ and ‘the station’ sound specific but they are ambiguous.

When CO19 reached the tube Jean Charles de Menezes was already seated, a surveillance officer shouted, “He’s here!” – easily interpreted as positive identification rather than a location update. The system had crossed the point of no return.

4) Consequence

An innocent Brazilian electrician with no connection to terrorism had been killed. Confusion and shock among officers and witnesses. All safety checks (identification, non-lethal options, warnings) failed.

5) Post-Consequence Management: Media, review and learning

The Metropolitan Police’s response after the shooting has been heavily criticised. The leadership made decisions that undermined public trust and prevented organisational learning.

Initial misinformation circulated uncorrected for days. The Met failed to quickly correct false statements claiming de Menezes wore a “bulky jacket,” “vaulted the barriers,” and was “running from police.” CCTV evidence later revealed he wore a light denim jacket, used his Oyster card normally, and walked calmly through the station. The barrier-vaulting was later thought to have been an armed officer, not de Menezes.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) was reportedly excluded from the immediate crime scene, hampering independent investigation. The dramatisation, Suspect, depicts officers being encouraged to coordinate their statements. It also shows a scene where one statement was found to have been altered, raising questions about whether damage control may have been prioritised over transparency.

These were unprecedented times for London, and individual officers were working in extremely difficult and high-pressured circumstances without the benefit of time nor hindsight, but the tragic events that day had led to an innocent man losing his life.

Conclusion: Understanding the Full Story

Applying TABIE’s ASAP model to the Stockwell shooting reveals the profound truth in James Reason’s observation about adding “the final garnish to a lethal stew whose ingredients have been long in the cooking.” The wheels of this tragedy were set in motion years before the trigger was pulled on July 22, 2005.

The ASAP framework demonstrates how the shooting resulted from a complex interplay of factors spanning multiple timeframes and organisational levels. From the post-9/11 development of Operation Kratos and the unprecedented terrorist threat context, through the morning’s cascade of operational failures, to the critical miscommunication that sealed de Menezes’s fate, each stage contributed essential ingredients to the fatal outcome.

Perhaps most importantly, the model reveals how the tragedy extended beyond the moment of the shooting itself. The Metropolitan Police’s post-incident response – characterised by misinformation, reported exclusion of independent oversight, and apparent coordination of officer statements – transformed an operational failure into a crisis of institutional trust that reverberates to this day.

This analysis has not been comprehensive, and details may not all be present or correct based on the dramatisation and public records consulted. However, it effectively demonstrates the value of systematic incident analysis that looks beyond individual actions to examine systemic vulnerabilities. Traditional “root cause” approaches might have focused solely on the officers who pulled the trigger or the surveillance team’s identification failures. The ASAP model reveals a much richer picture of how organisational decisions, policy frameworks, technological limitations, and cultural pressures combined to create conditions where tragedy became almost inevitable.

For practitioners of incident investigation – whether in policing, healthcare, aviation, or industrial settings – the case underscores the critical importance of examining both the latent conditions that create vulnerability and the organisational responses that determine whether incidents become learning opportunities or recurring risks. Only by understanding the full sequence, from precursor conditions to post-consequence management, can we hope to prevent similar tragedies and systemic industrial accidents in the future.

If you want to find out more about the TABIE methodology and the ASAP model you can do so here: https://www.humanreliability.com/downloads/tabie-a-task-analysis-based-incident-evaluation-technique/

Disclaimer

This blog post is written for educational and analytical purposes to demonstrate incident investigation methodologies. The analysis presented here is based on publicly available information about the tragic shooting of Jean Charles de Menezes in 2005, including official reports, inquests, and court proceedings that are part of the public record. The Disney+ dramatisation, Suspect, renewed interest in this incident and events which have been reported here, which may not be accurate.

This post is not intended as a comprehensive investigation of the incident, nor should it be considered a definitive account of events. The TABIE methodology application shown here is illustrative, designed to demonstrate analytical techniques rather than to reach conclusions about individual or organisational culpability.

The author acknowledges the profound tragedy of this event and its lasting impact on Mr. de Menezes’s family and all those affected. This analysis is conducted with respect for all involved and with the intent of contributing to better understanding of how systematic approaches to incident analysis might help prevent similar tragedies and systemic industrial accidents in the future.

This blog was drafted with the help of Claude.ai Sonnet 4.0